Most of the things I've covered previously have been either from the early 20th century, or perhaps the very late 19th century. This time, I'd like to go back a bit further in order to discuss a fascinating man, and a fascinating newspaper, that had quite an effect on newspaper illustration at the time, and continued to have an effect for many years.

The newspaper was one in Indianapolis, called The Freeman, and was African-American owned and operated. It was first published in 1888 by Edward Cooper, and while there were several African-American papers in various cities at the time, The Freeman was the only one that was illustrated. That was its boast, at least, and that fact certainly helped its publicity and circulation.

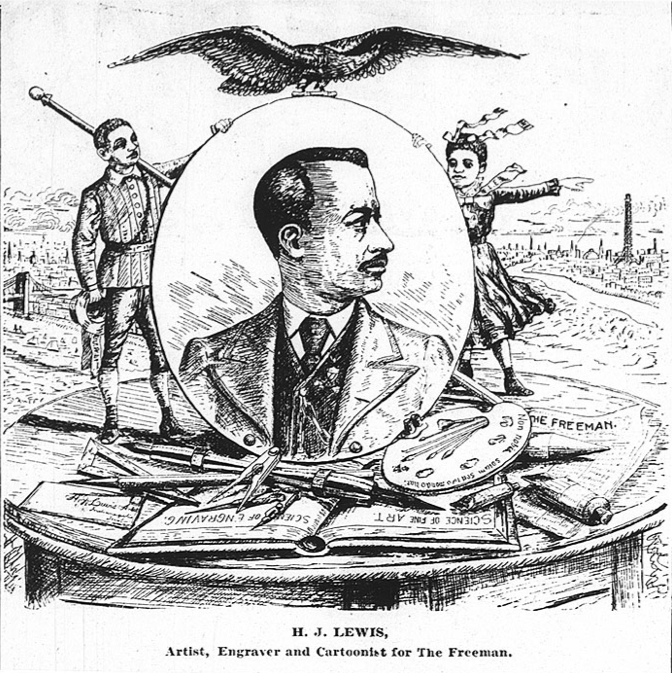

The most prominent illustrator at The Freeman was Henry Jackson Lewis, who was born, according to the best records anyone has, sometime around 1837 in Water Valley, Mississippi, as a slave. Very little is known about his early life, apart from an accident as a child which left him blind in one eye. Around 1863 he gained his freedom, fought in the Civil War, and ended up in Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where he learned to draw. Early on in his art career, he sold drawings to publications such as Harper's Weekly and Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. His work was noticed by mainstream white publications as well as black publications, and most interestingly, no matter where his work was published his name was actually attached to it. Edward Palmer, archeologist at the Smithsonian, was quite aware of his talent, and enlisted him to sketch Native American burial grounds in Arkansas, as well as to draw maps of several surrounding states. While in Arkansas, he also worked at the Arkansas Gazette in Little Rock, and sold several drawings to the national magazines Puck and Judge.

In 1889, he moved to Indianapolis to begin work for Edward Cooper's The Freeman, and became what many have called the first African-American political cartoonist. One reason for this appellation was his sharp rebuke of president Benjamin Harrison, as well as his artistic statements on race relations in general. Another reason, however, was how his artwork, as well as that of other Freeman artists, depicted African-Americans.

From the early days of newspaper cartoons all the way to nearly the middle of the 20th century, black people tended to be depicted in comic strips as distorted caricatures with uneducated dialects. Stereotypes in cartoons and comic strips obviously abounded, but even in "realistic" action and adventure comics, no favors were done to black characters. Only comics that appeared in black newspapers actually depicted them as real people with regular lives. In the 20th century, the expansive comics sections of black newspapers such as the Pittsburg Courier and the Chicago Defender were well known for doing this, but in 1889, it was only ever done in the pages of The Freeman.

While it seems a small thing, showing an African-American as a person, who was just as much of one as any white person, was a serious political statement. It was one that Lewis continued to strive to make throughout his career, even after it became threatened by Edward Cooper's reticence to let him continue. Cooper felt an increasing need to appeal to the masses in order to increase readership, and the statements in the Freeman became less and less bold over time. Still, Lewis continued to stay true to his convictions for as long as he could.

Lewis only worked at the Freeman for about two years before he died in 1891, but he produced nearly 200 cartoons and illustrations for them in that time. The Freeman itself continued until 1892 under Cooper, and lasted until 1926 under later publisher George Knox.

For more information:

Henry Jackson Lewis at Indiana Illustrators

Henry Jackson Lewis at the Encyclopedia of Arkansas History and Culture