Click the image to see a larger version.

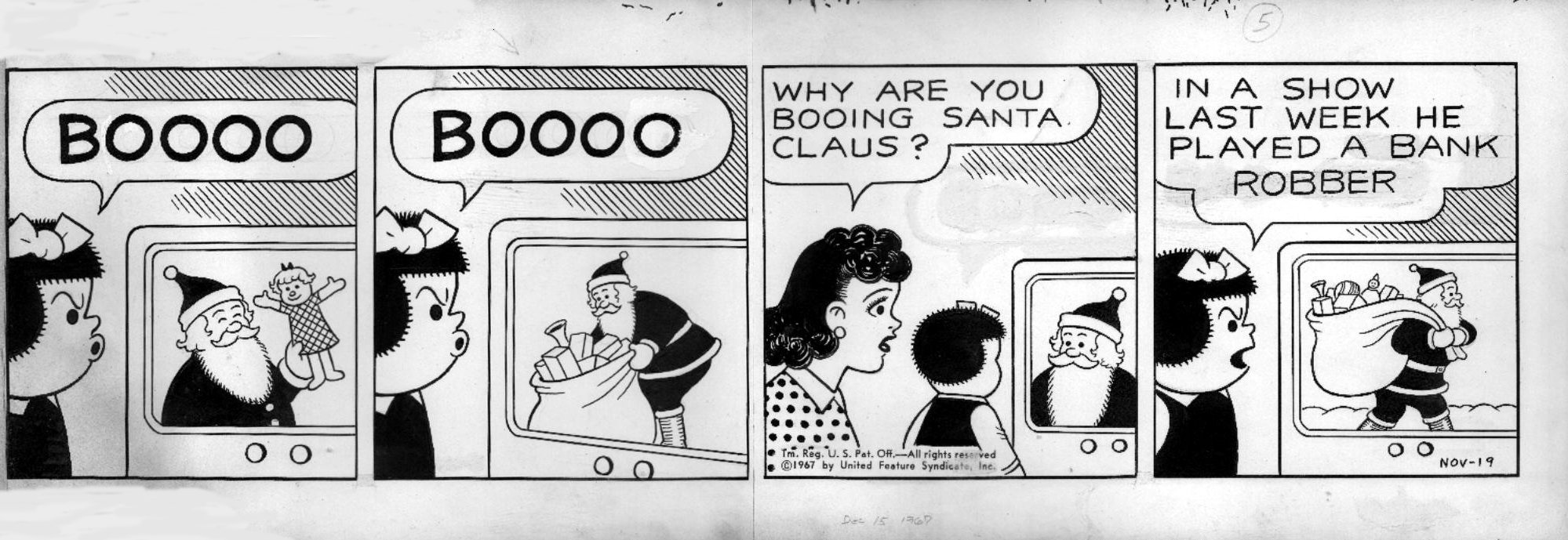

Nancy demonstrates an impulse that I think we've all had at one time or another. Some actors seem to always play a certain type of person, and we come to expect that of most of them, so it's a bit jarring at times when we see one playing against type. I've certainly had that experience before. It would definitely be difficult if you recognized the person playing Santa Claus as someone who had not been so kind and jolly in a different role. It seems like the Santa outfit would only be a disguise and a way to sneak into and rob the toy store.

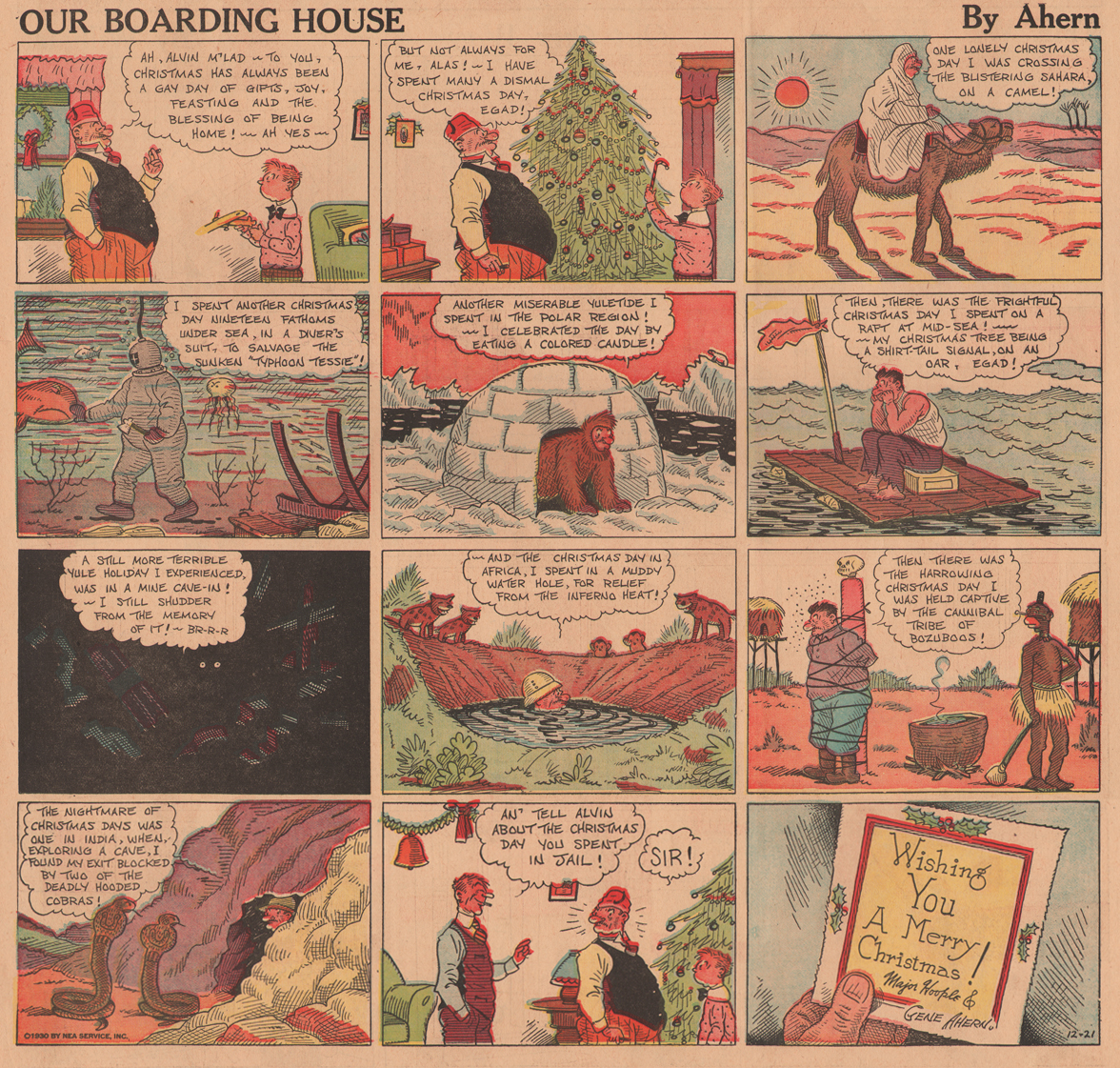

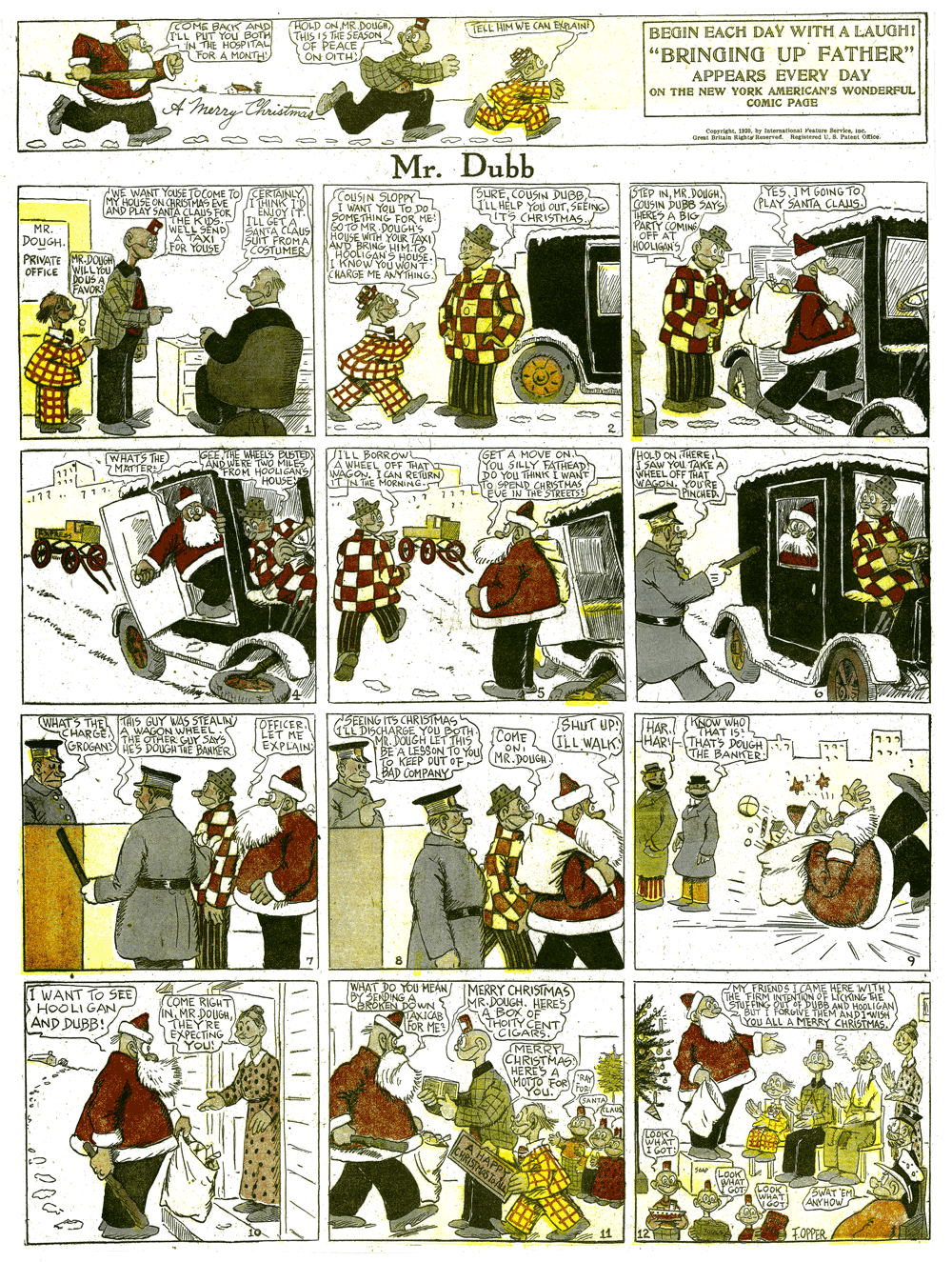

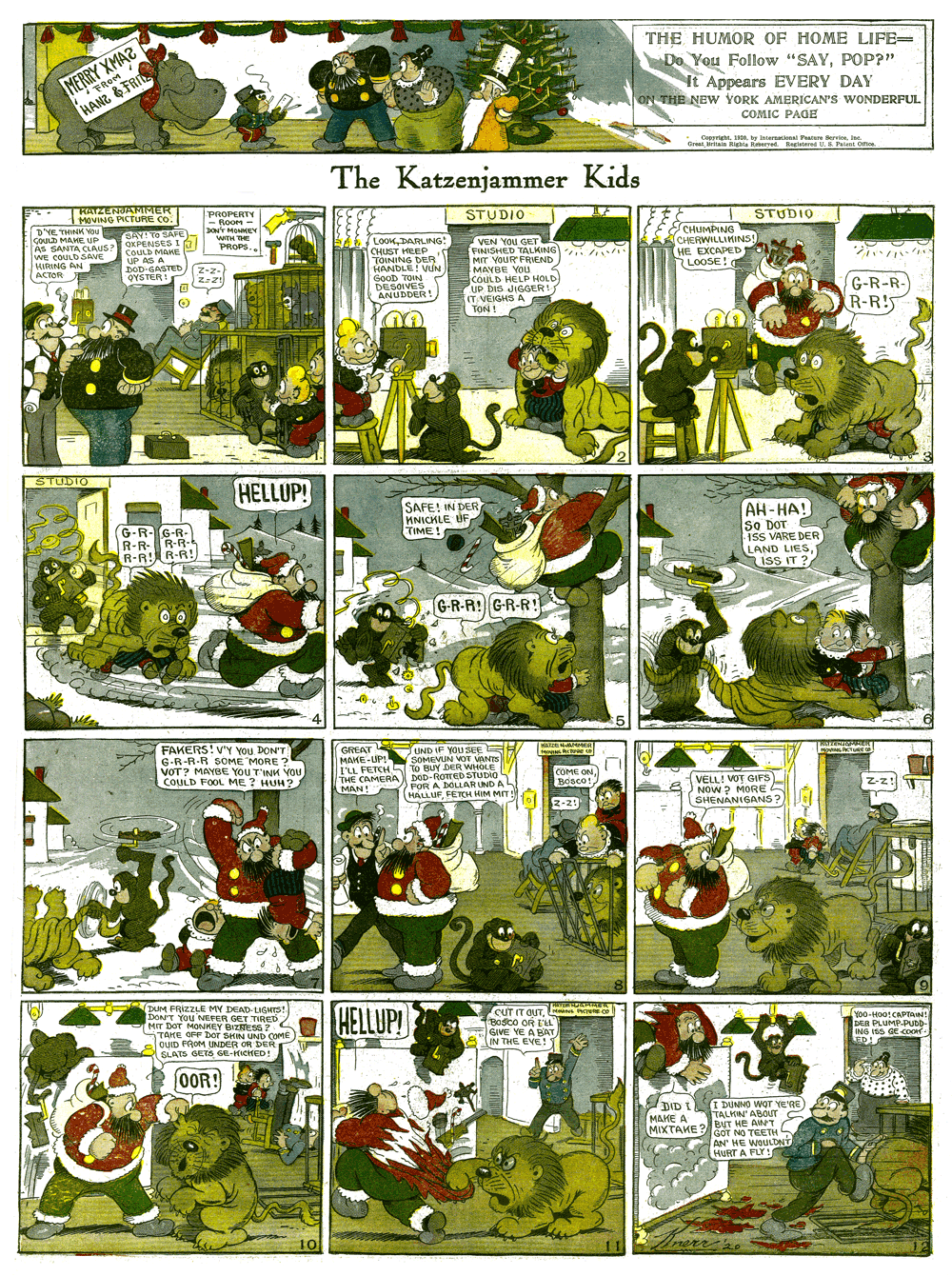

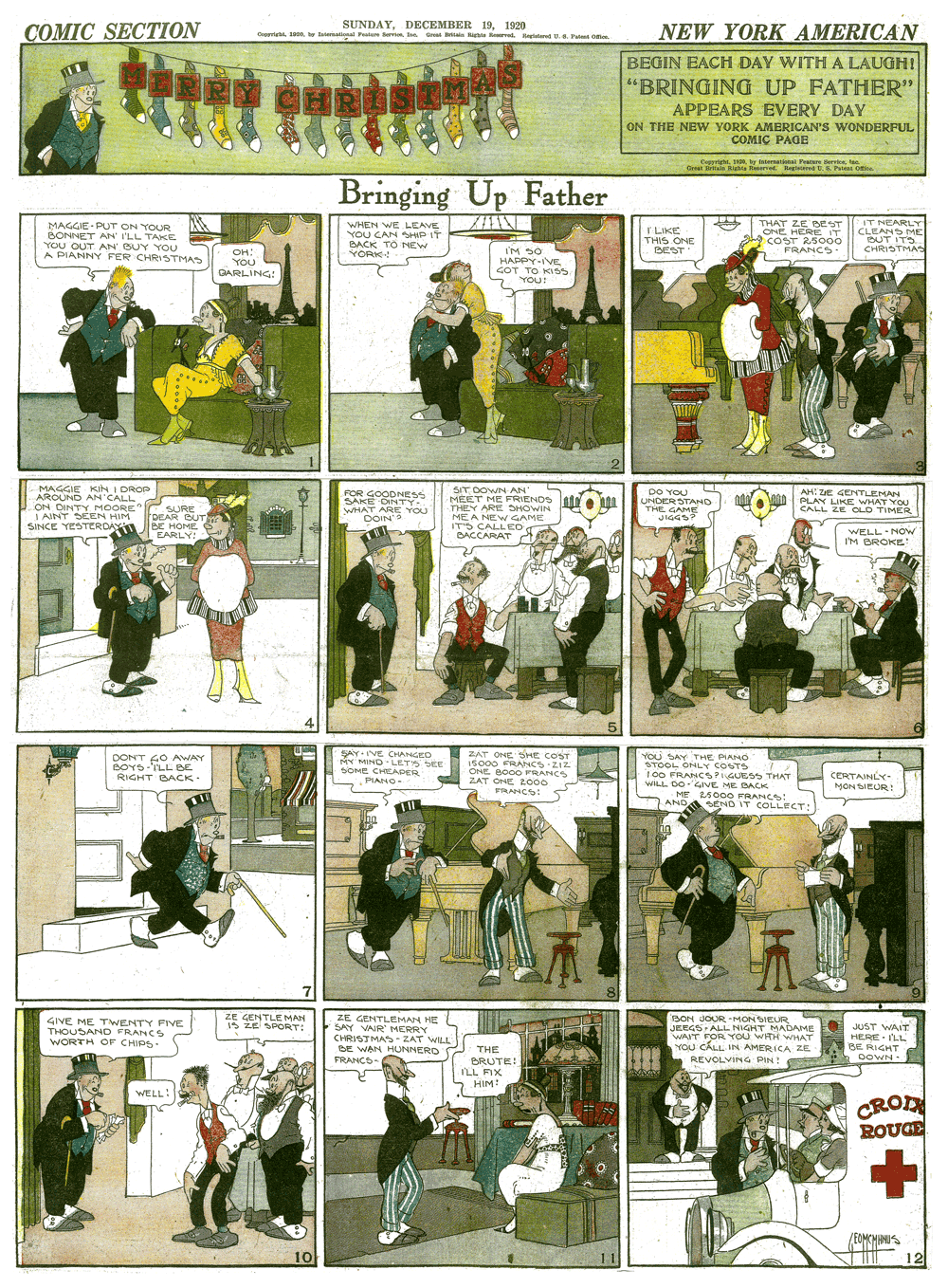

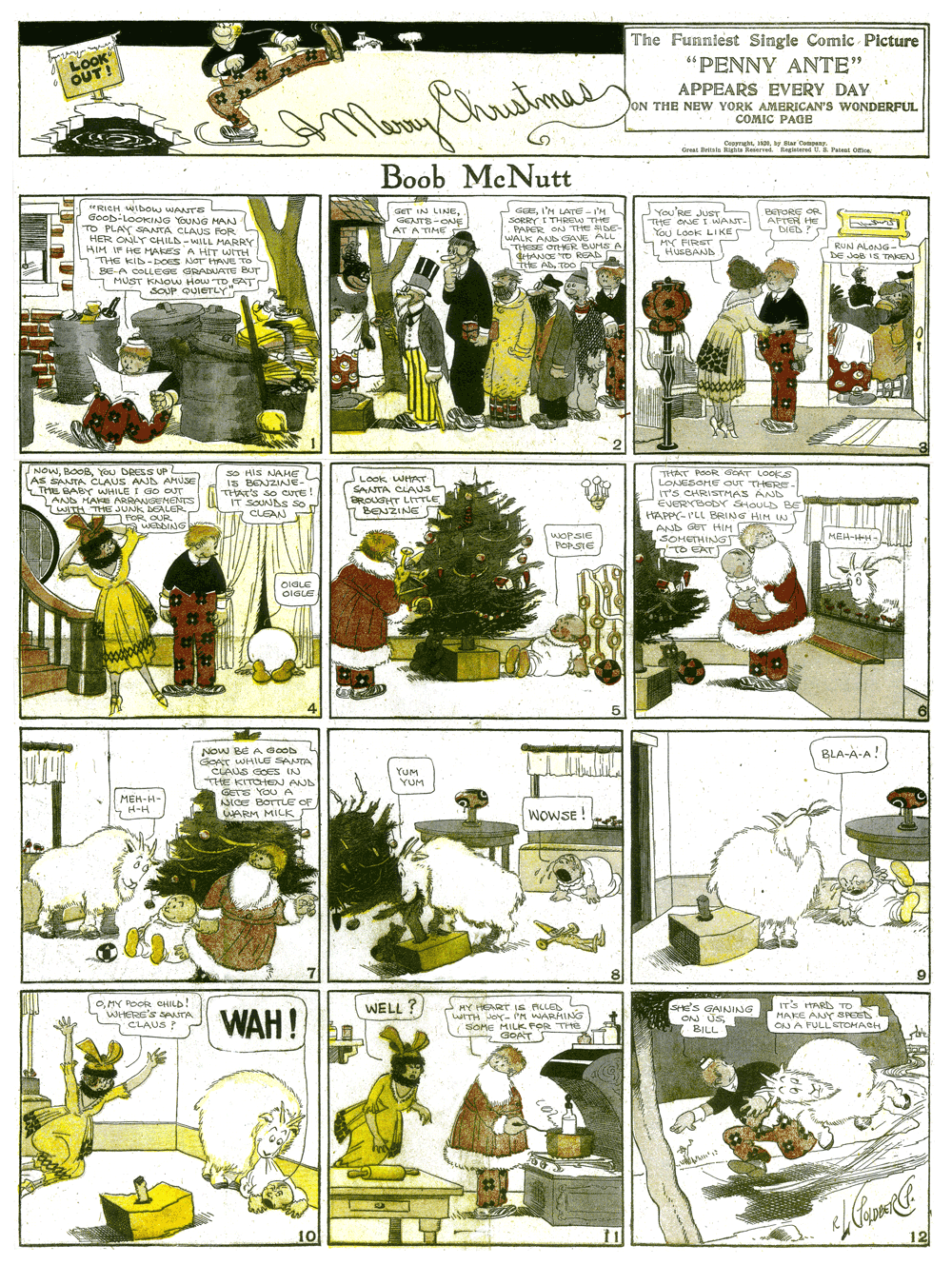

Interestingly, this is a joke that Bushmiller had used previously, in a strip that was published 12 years earlier:

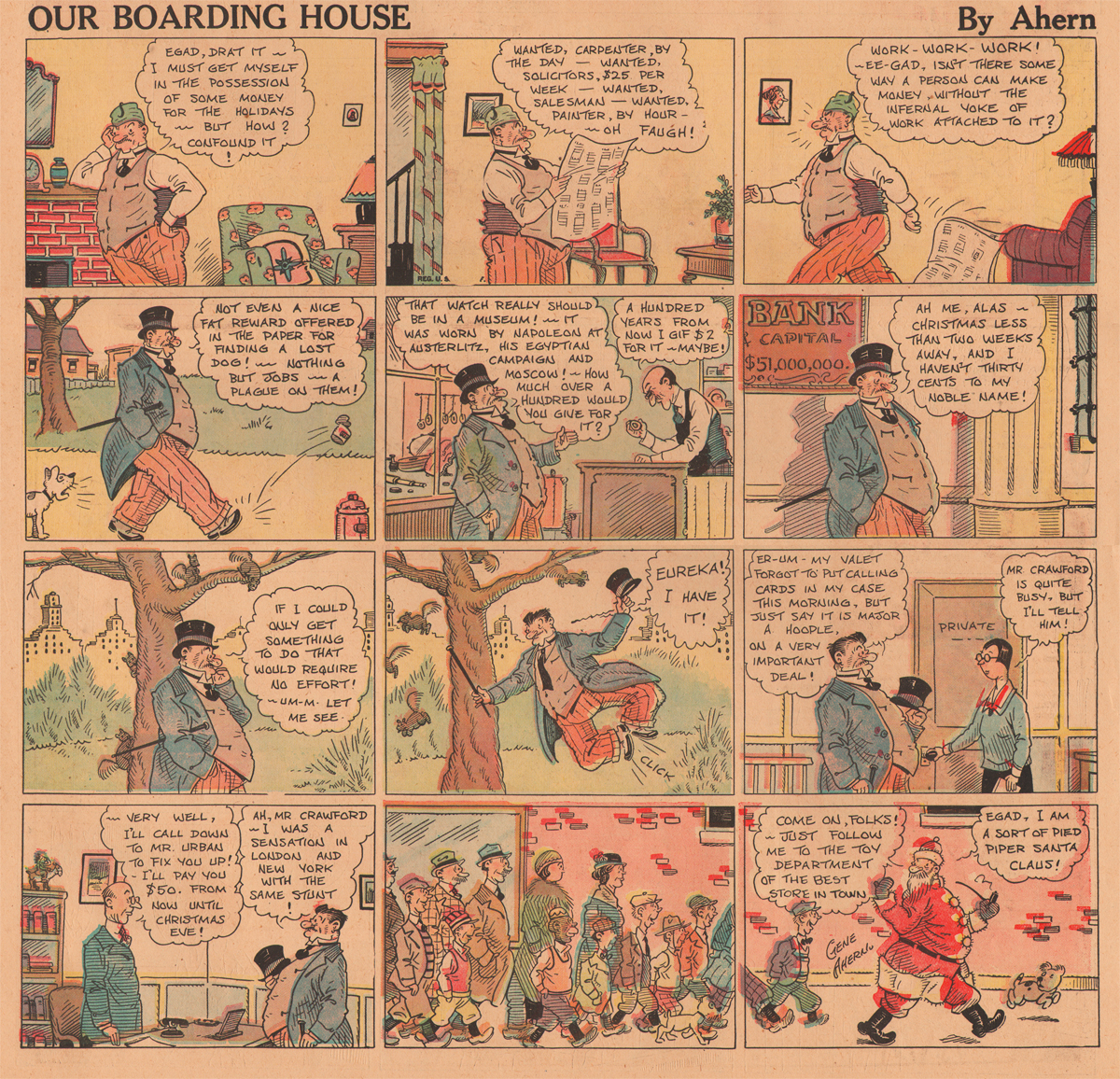

He just updated it to be used with Santa Claus. It still works, though, in my opinion, and it isn't a very surprising thing to see. Cartoonists who have been doing their comic strips for quite a while do tend to reuse many jokes they had used before. In fact, legacy cartoonists drawing a comic strip created by someone else will often dig back into the creator's archives to resurrect an old joke for a new audience. They obviously hope that people won't notice, and most people don't.