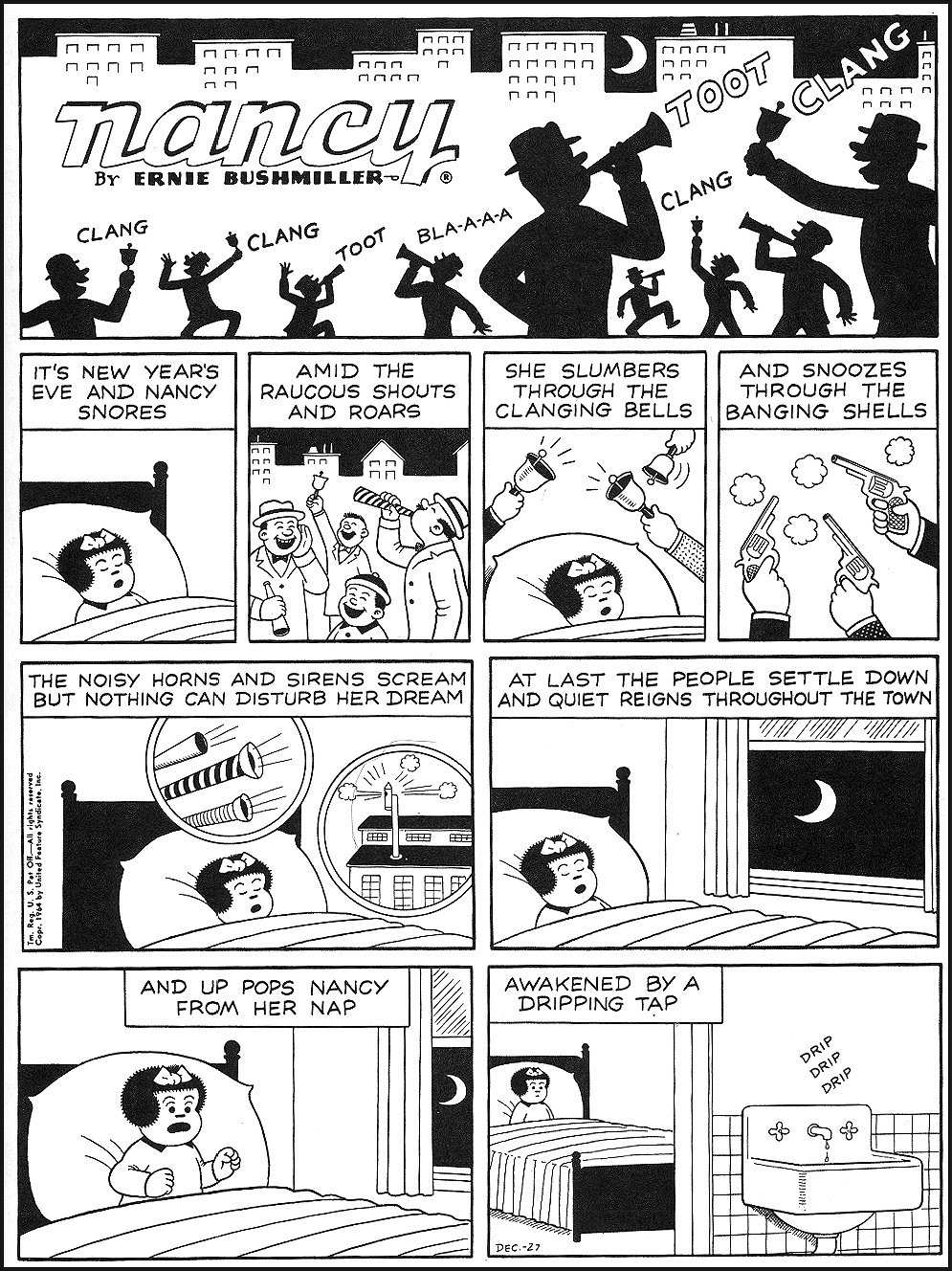

Click the image to see a larger version.

The final Nancy comic of this year.

I have one question, though: Do people still shoot off guns on New Year's Eve, or was that just something they did in 1964? I'd think you'd have enough things that make loud noises that you could probably forego the firearms. Fireworks would probably be sufficient, and would look cooler. That seems to be the prevailing theory around here, anyway.

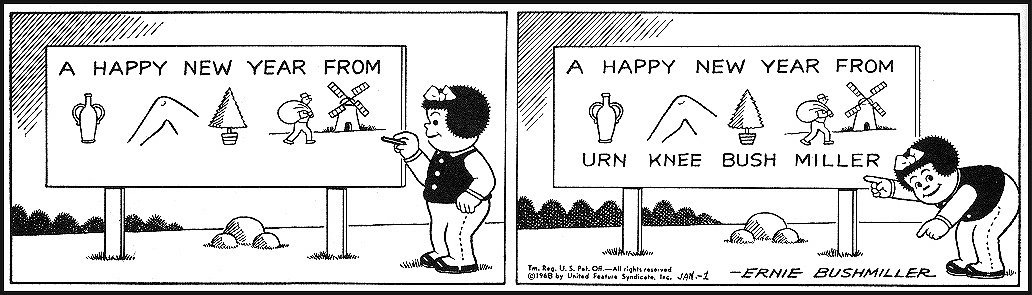

Happy New Year, everybody!