Click the image to see a larger version.

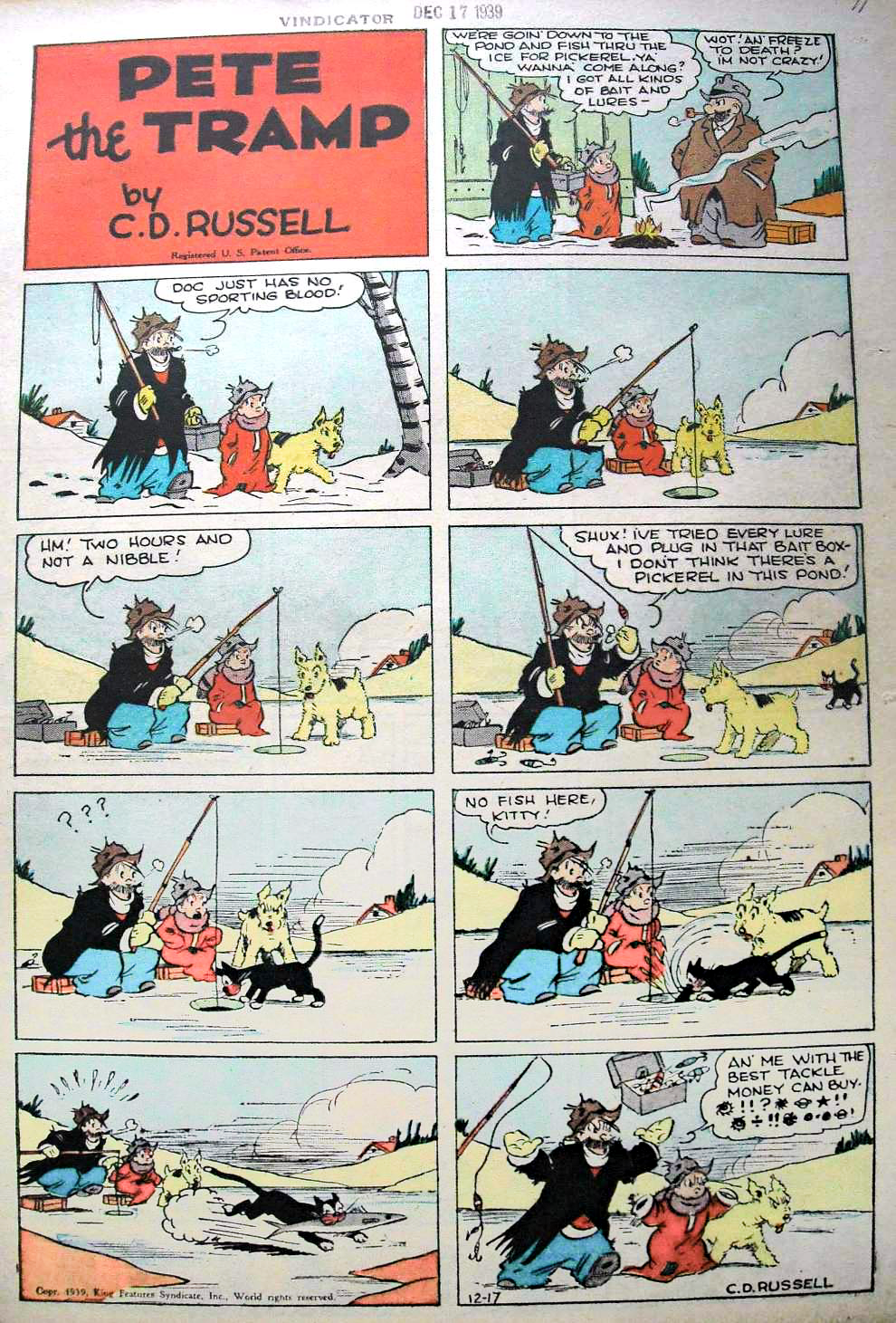

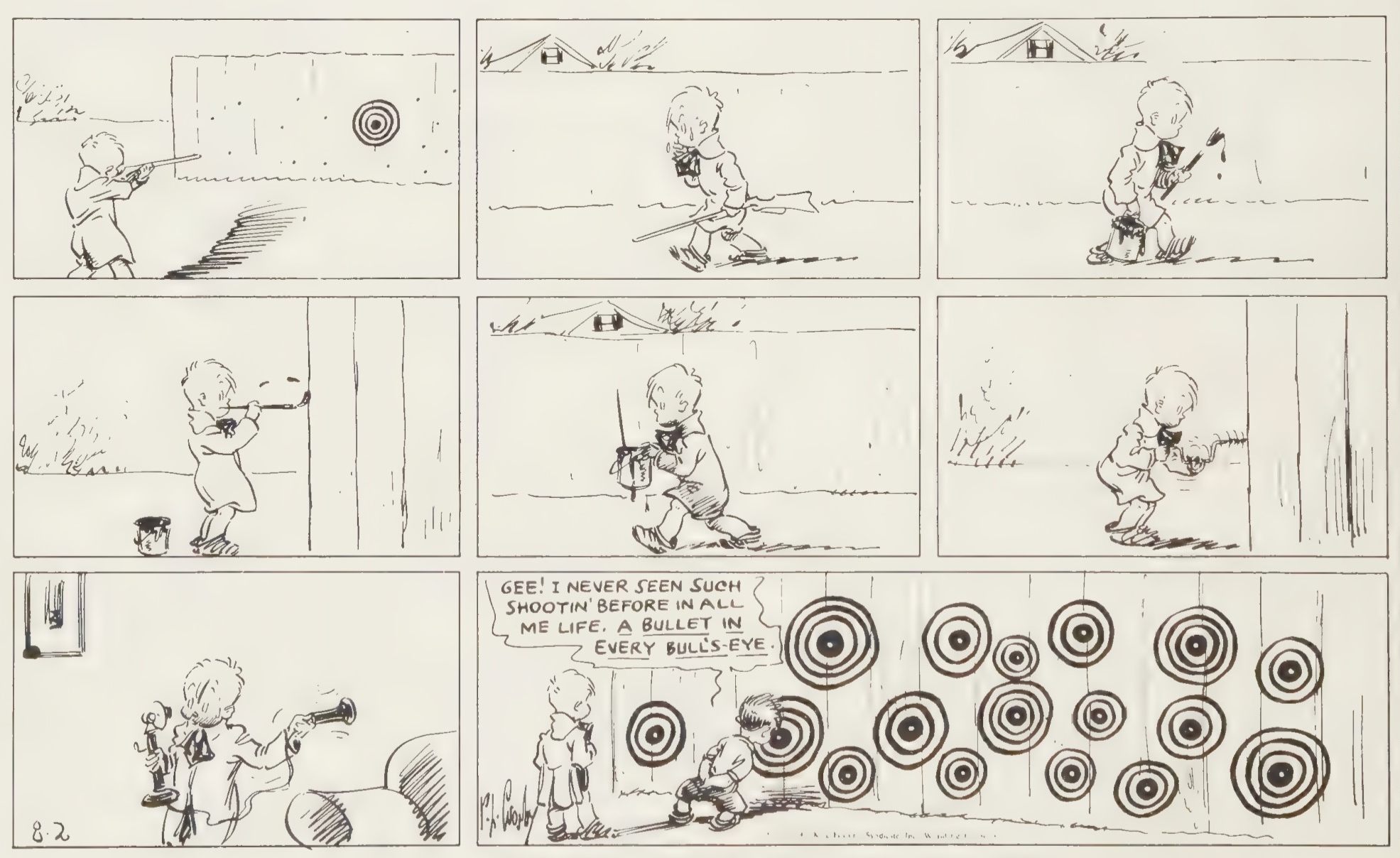

Pete the Tramp often appeared with a terrier dog as well as what appears to be an orphan boy. The dog is usually referred to by Pete as "boy," though no name is ever given. It bears a resemblance to the dog that appears in the Pete the Tramp topper strip originally titled "Bumps" and later retitled "Pete's Pup." Oddly, despite the name of the topper, that dog does not appear to be owned by Pete, so the name of the dog that Pete is seen with remains a mystery. I was also unable to find anything about the child, though I have concocted a head canon. C.D. Russell was an assistant to Percy Crosby on his strip Skippy, so I imagine this child is one of the kids that Skippy would have hung around with. Until I can discover who he really is, that's what I'm going with.

As for this particular strip, I like it a lot. I love the third panel of the three of them sitting there in silence. I love the last panel that shows all three of them with equally exasperated expressions. I love how, when the cat arrives, none of them get up and do anything about it. In most other strips, someone would get up and shoo the cat away, but here they all just sit and watch it. Maybe, given the cat's success, they'll invite the cat to go fishing with them next time.