I have always maintained, and will always maintain, that comic strips of any era can be considered fine art. There's nothing that separates the art that you see in the newspaper and the art that you see in a museum apart from one being in a frame and one being in print. I feel this opinion of mine is bolstered by the fact there are those who are considered fine artists who also created newspaper comic strips.

Lyonel Feininger certainly deserves the label of fine artist. Born in New York, he was sent to Germany at 16 to study music, but ended up studying art instead. He studied at various art schools in Berlin and Paris. He was affiliated with several German Expressionist groups, including the famous Blue Four, which included himself, Paul Klee, Wassilly Kandinsky, and Alexej von Jawlensky. He helped found the Bauhaus school and was the only person to teach there from its inception all the way until it was forced to close. He worked in several different media, including oil, woodcut, charcoal, and ink, in an art career spanning several decades. One of his paintings, The Green Bridge, even sold at auction in 2001 for an amazing £2.42 million.

Knowing all this, his is obviously not a name anyone would expect to see on a newspaper comic strip. It's a bit of a shock, then, when one realizes that Feininger created two of them.

At the turn of the 20th century, American newspapers would often reprint cartoons and caricatures from European publications, mainly because it was cheap to do so. Erroneously believing that this was done because it was in high demand among the readership, The Chicago Tribune decided that, instead of reprinting, it ought to enlist some European artists and writers to create material for them. Several German magazine cartoonists and illustrators were hired to create both one-off gags as well as some continuing series. Feininger, in order to pay his bills, had been working as a caricaturist in Germany for many years, and was hired by the Tribune along with the other artists.

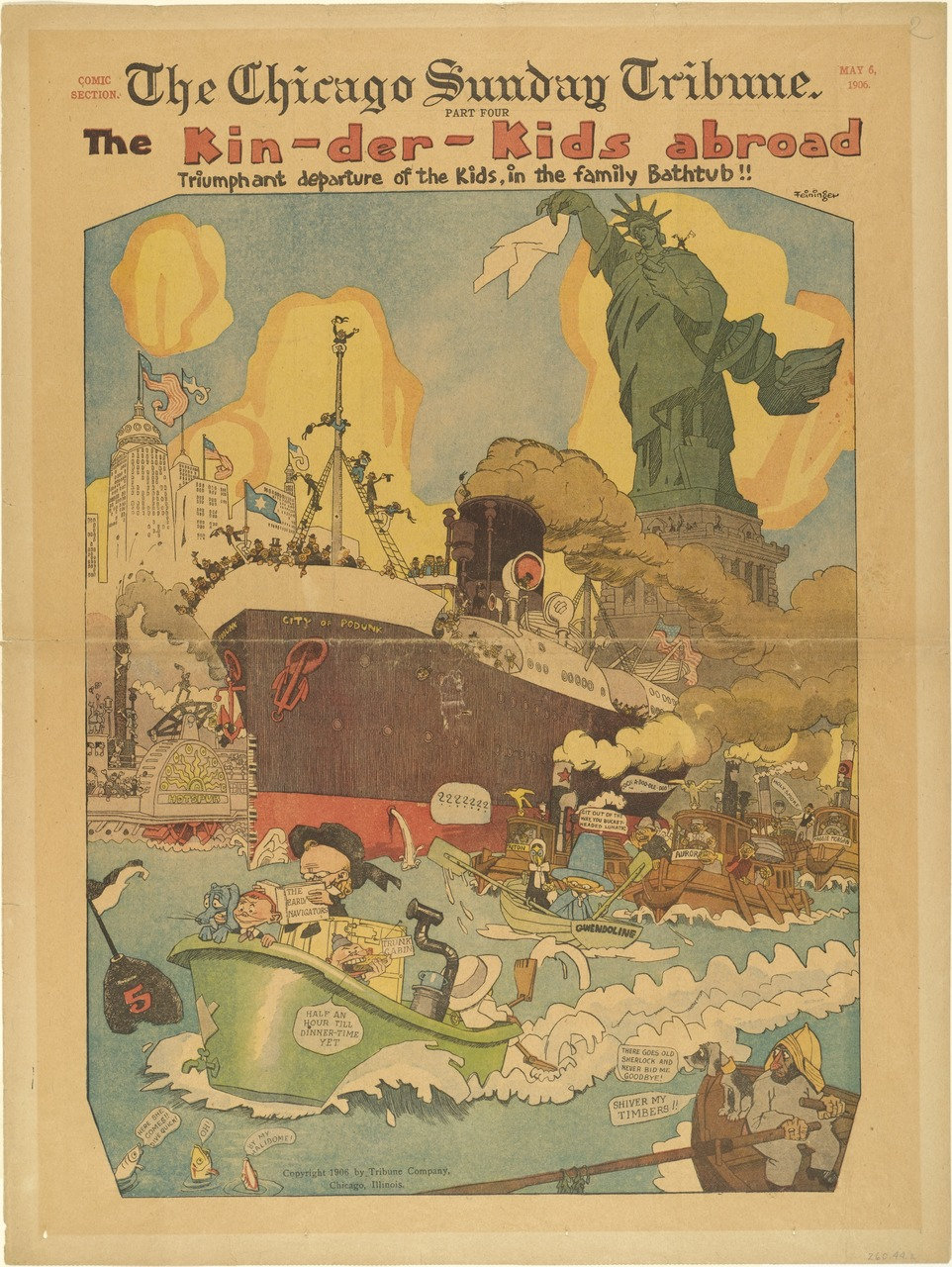

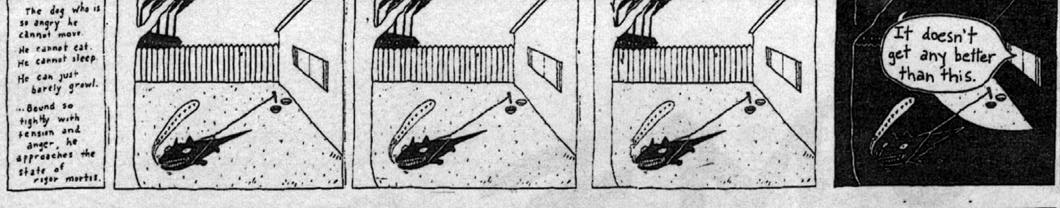

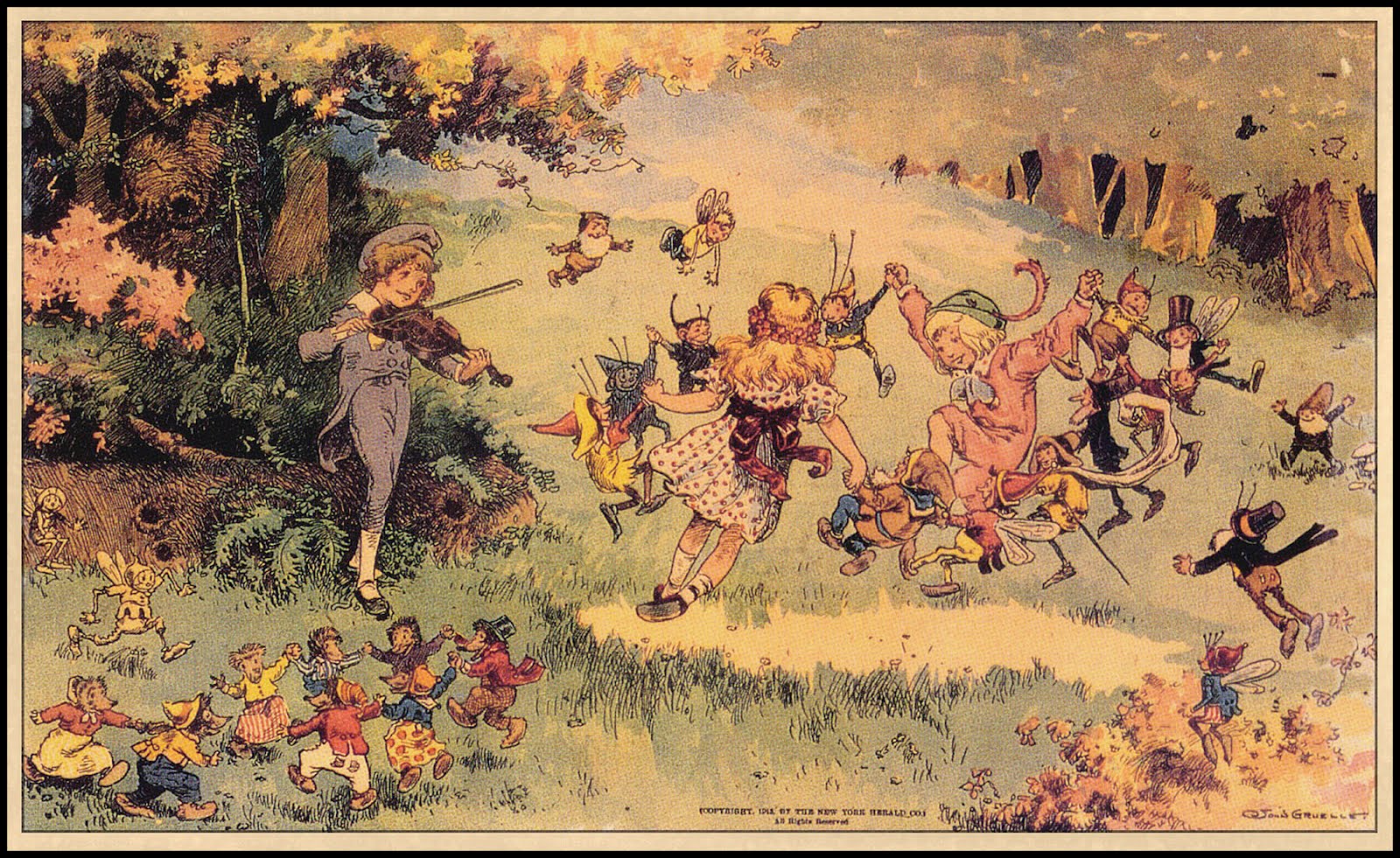

The two comic strips that he created were "The Kin-Der-Kids," which ran from April to November of 1906, and "Wee Willie Winkie's World," which ran from August of 1906 to January of 1907. "The Kin-Der-Kids" was an adventure story involving some kids, a mechanical boy, and their talking blue dog travelling the world in their bathtub. It's definitely as strange as it sounds, but not nearly as strange as "Wee Willie Winkie's World," which revolved around the titular Willie and the incredibly surreal world that he lived in. In it, everything was alive, and anything that could be given a face and a voice was. This meant that Willie often ended up being the least interesting thing in the strip. The art on both strips is as good as you'd expect, and certainly rivals the other great cartoonists of that time such as Winsor McCay and Richard Outcault.

Unfortunately, due to troubles with the syndicate, both features were cancelled after very short runs. The cancellation wasn't entirely bad for Feininger, however, who shortly afterward began his art career outside of comics. It is interesting to notice, however, how his work in comics influenced his later work, as well as how his previous art training influenced his comics.

For more information:

Lyonel Feininger at Toonopedia

Lyonel Feininger at Comiclopedia

Wee Willie Winkie's World at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum

Lyonel Feininger works at Wikiart

Lyonel Feininger at the Museum of Modern Art

Lyonel Feininger works at the Museum of Modern Art German Expressionism collection