Stan and Jan Berenstain (not Berenstein, and no we will not be discussing the Mandela Effect today) are of course best known for creating the series of children's books The Berenstain Bears. Books in the series have been published since the 1960s, and are still published now, overseen by Stan and Jan's son Mike. A much less well known fact is that the Berenstains had a fairly long cartooning career prior to creating the Bears, even creating a syndicated newspaper comic.

Despite both growing up in Philadelphia, and at one point even living in the same neighborhood, they didn't meet until they were college students, on the first day of drawing class at what was then called the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art (later called University of the Arts, and which sadly closed down in 2024). Shortly thereafter, they would be separated by World War II, as Stan was drafted into the Army, but they would still put their artistic abilities to use. Much of Stan's time in the Army was spent at a hospital as a medical illustrator, making detailed drawings of soldiers who had undergone facial reconstruction surgery. As you can imagine, the work could be quite unpleasant, so to keep things light he created cartoons featuring a bumbling, incompetent soldier character called Oglethorpe, which would end up getting published in several Army newspapers. Not satisfied with just being published in Army publications, he also sent some cartoons to a magazine called the Saturday Review of Literature, and was paid $35 per cartoon (which, by 1940s standards, was pretty good, especially for a soldier).

While Stan was in the Army, Jan also contributed to the war effort as a riveter, as well as a mechanical illustrator for the Army Corps of Engineers. When Stan returned home in 1946, they were so happy to be reunited that they were married less than two weeks later. Encouraged by Stan's earlier success at selling cartoons to a magazine, the two decided to become a cartooning team and submit to as many magazines as they could.

They were not met with very much initial success. No major magazine wanted to buy their work. They were able to consistently sell to the Saturday Review of Literature, but mostly because the cartoons they submitted were mainly about art and literature. In his book on their early cartooning work, their son Mike recounts a meeting that Stan had with an editor of The Saturday Evening Post. He asked Stan if he had ever actually read their magazine, and when Stan replied that he had, the editor said he found it quite surprising given the kinds of cartoons that he sent in. He praised the overall quality of the work, but said that what they wanted was cartoons about families and parents, not art and culture. With this in mind, Stan and Jan decided to be a bit more targeted in their humor, to appeal to the audience that read the magazines they were trying to sell cartoons to.

The Berenstains weren't parents yet, so their ability to write jokes from the perspective of a parent was limited. Around this time, they took jobs as instructors at the Settlement School in South Philadelphia. Their experience at the school, as well as thinking back to many of their own experiences as children, inspired them to write jokes from the perspective of kids. Unlike their previous batches of cartoons, these proved to be far more popular, and major magazines such as the aforementioned Saturday Evening Post and Collier's began buying them. One cartoon editor suggested that it would also be good publicity at family magazines to reinforce that they were a husband and wife team, so they began signing all of their work "The Berenstains." This new direction helped them go from selling to only one or two no-name magazines to regularly selling to the biggest names in the business.

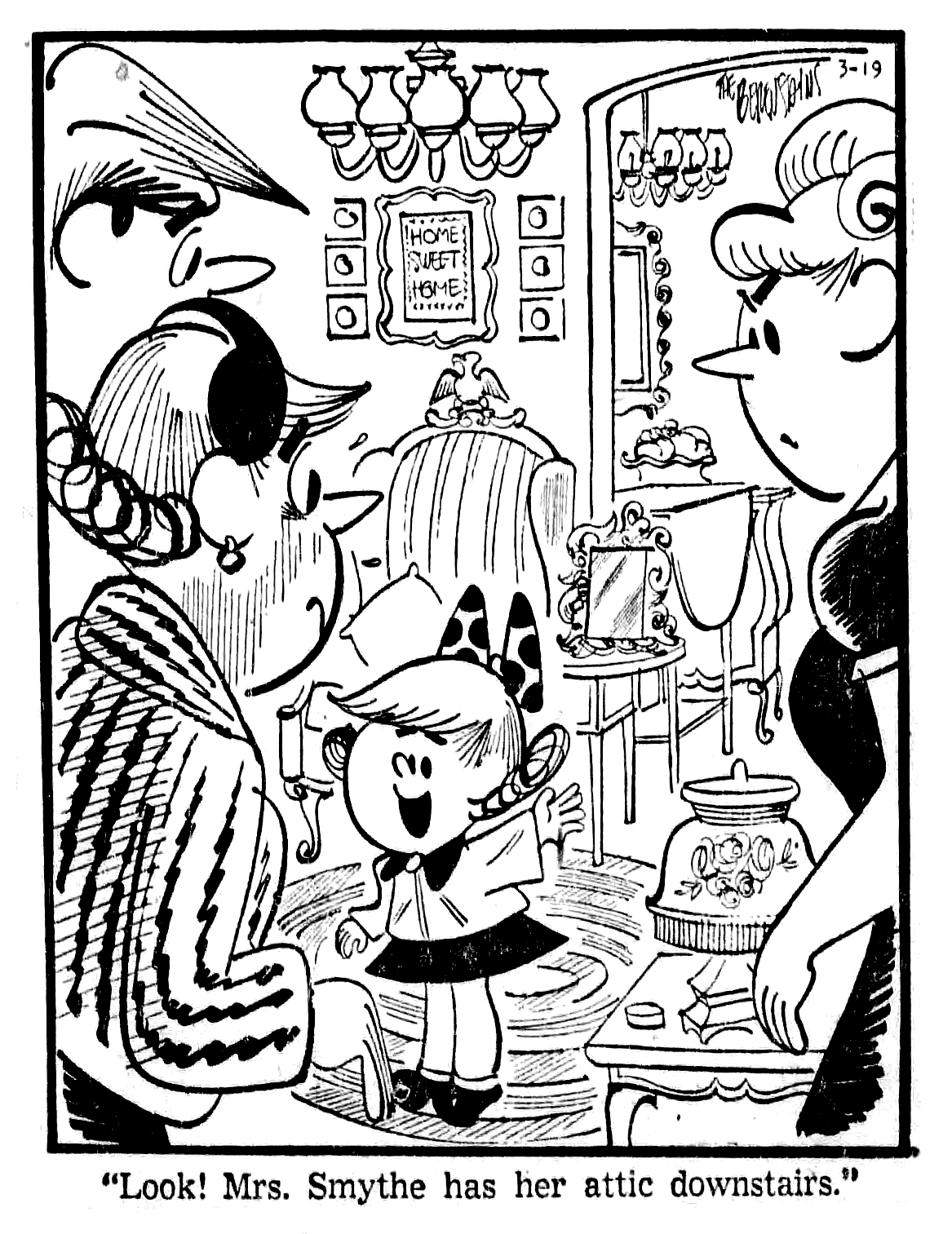

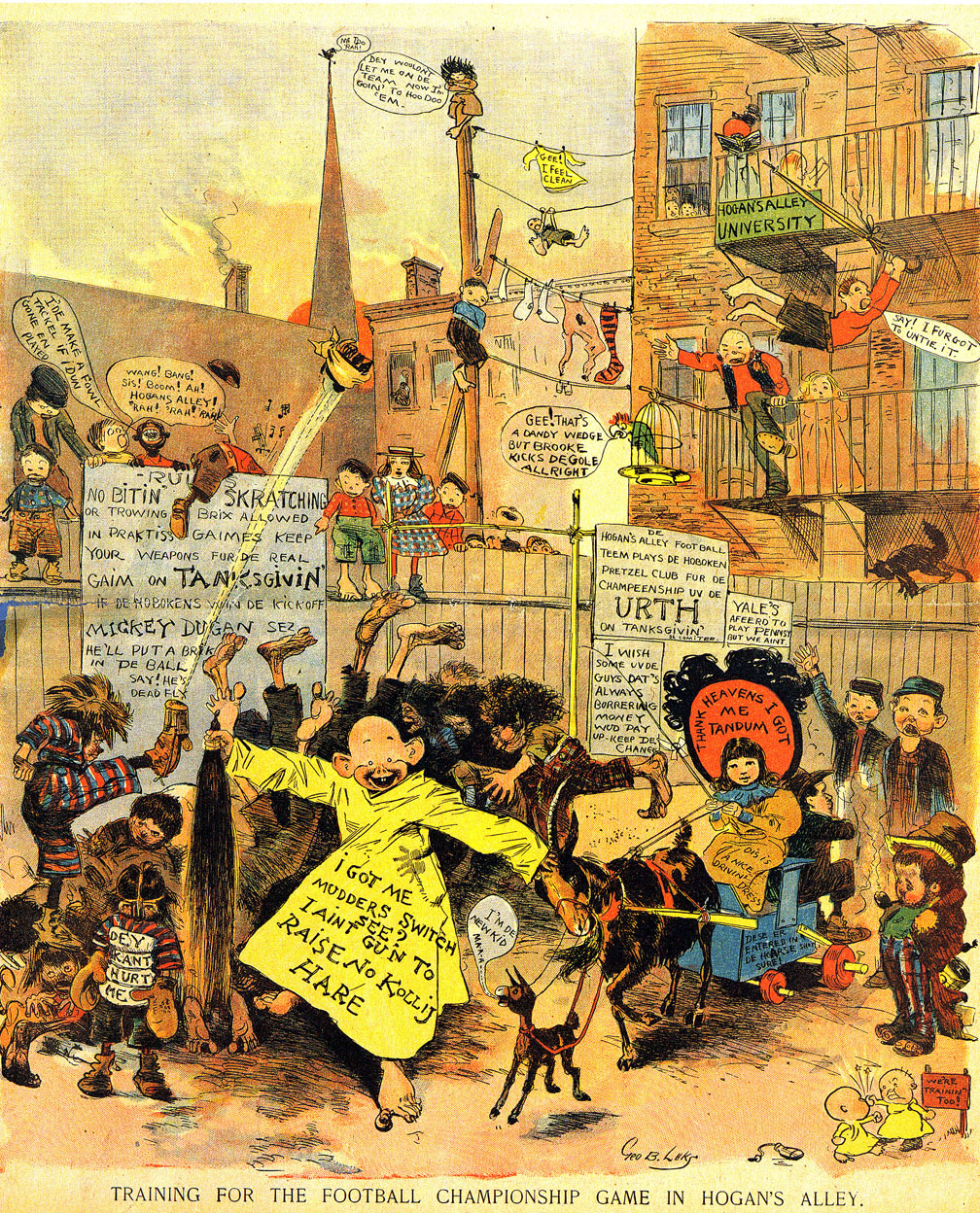

A lot of their success came from Collier's Magazine, where they gained popularity for a series of full page cartoons which depicted large scenes of groups of children playing in various ways, such as at recess, on a frozen lake in winter, and in the school gym. In addition to the interiors, they were able to get many cartoons on the cover of the magazine, which only increased their notoriety. This led to their main output being for Collier's, and their cartoons becoming a regular feature in every issue. A popular recurring character in their Collier's cartoons was a young girl named Sister, a tomboyish, no-nonsense type reminiscent of Little Lulu or Nancy. She has over the years often been compared to Dennis the Menace, though she predates him by a couple of years.

Around this time, in 1951, the Berenstains were also contacted by book publisher Macmillan, who asked them to do a book of cartoons about parenting. They had a child and were parents by that time, and where therefore able to pull from that experience to create a book called "The Berenstains' Baby Book." Multiple similar humor books followed, including a collection of the Collier's Sister cartoons. While their cartoons of that era didn't have very many recurring characters, Sister was certainly their most popular. This led them to consider doing something they had never done before, which was submit the cartoons for syndication at a newspaper.

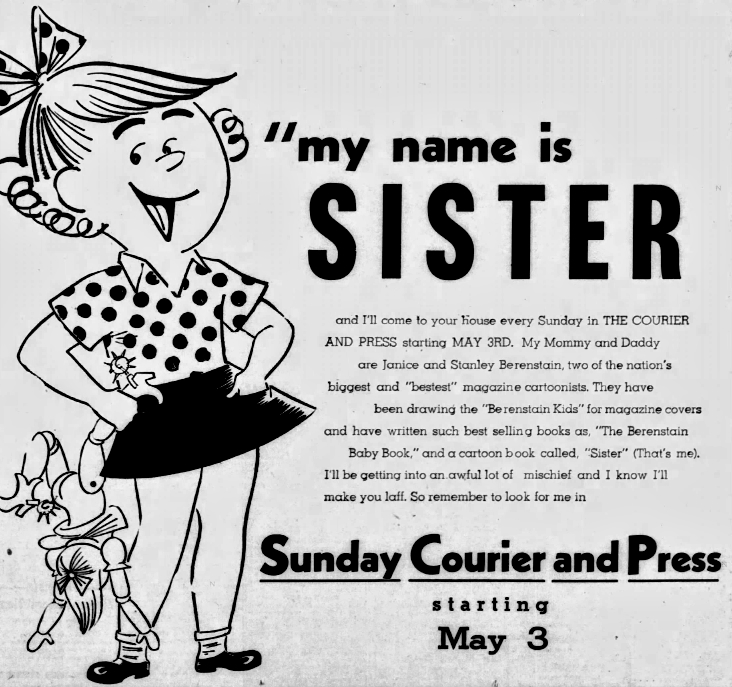

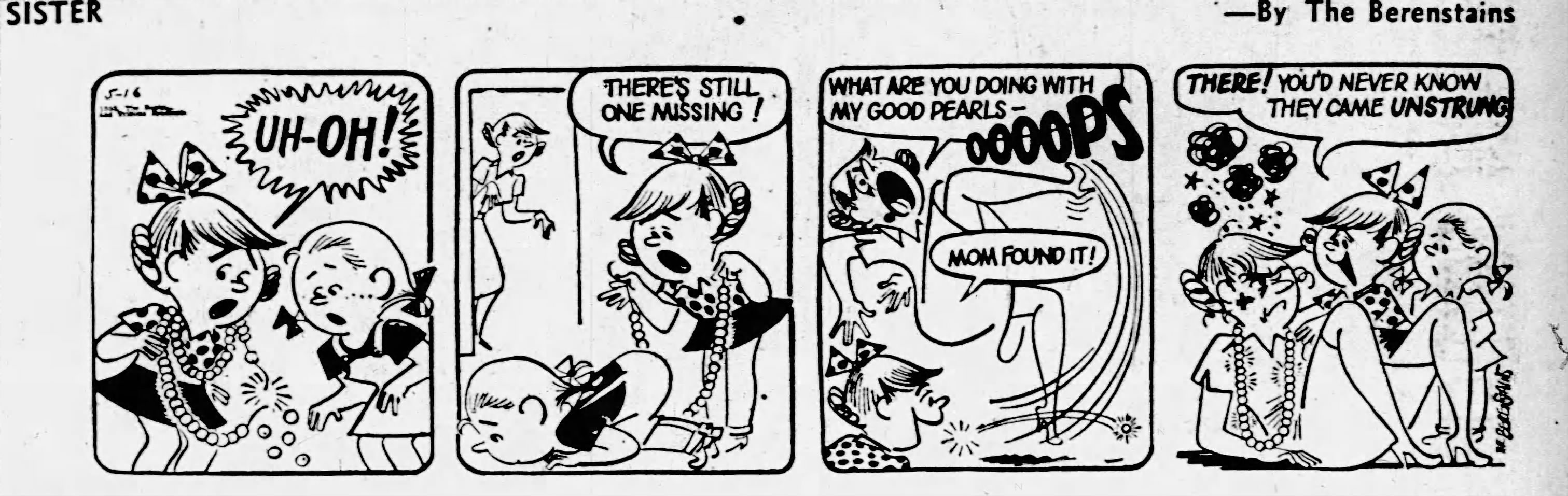

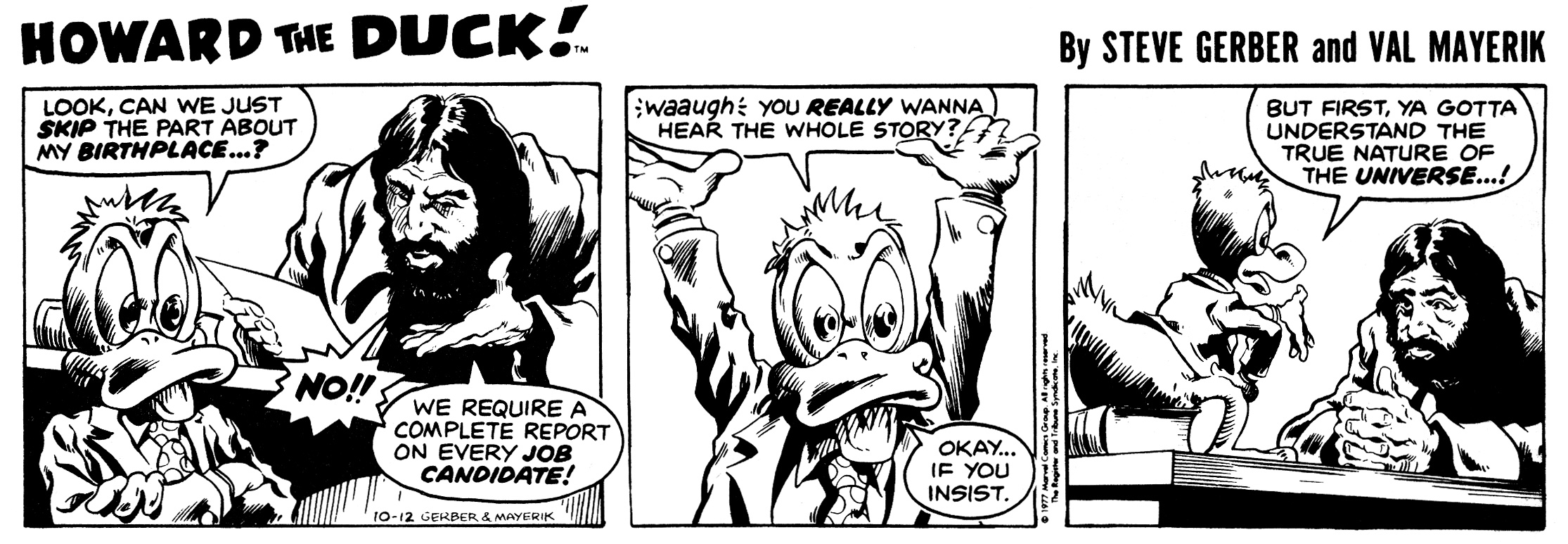

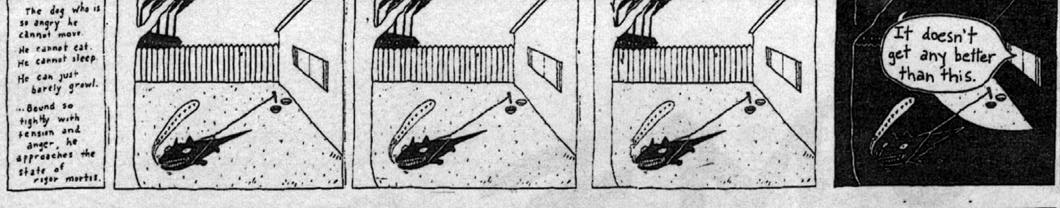

The comic strip "Sister" was picked up by Register and Tribune Syndicate, and the first strip ran on April 6, 1953. While their magazine cartoons were generally a single panel, the daily newspaper comics were always two to three panels, and of course several more on Sundays. This was the case for the first year, at least. In July of 1954, the dailies switched to a single panel format, though the Sundays continued to be multiple panels. This is kind of a shame, because I think the Berenstains did a better job when they had the space to build up to a punchline rather than just immediately deliver a gag. Comic strip historian Allan Holtz has a low opinion of the strip, and thinks many of the gags were actually "recycled" from Dennis the Menace, though I think Sister has a different kind of charm to her than Dennis does. He also notes that she seems to be misnamed, given that she's an only child, which I can't argue with.

Unfortunately, most readers and newspaper comics editors had much the same opinion as Holtz, as Sister never ran in very many papers over its lifetime. Advertisements for the new strip in newspapers always mentioned the Berenstains' magazine cartoons, clearly hoping to pull in some of the magazine readers, but this didn't seem to do much to increase readership. After a short while, Stan and Jan found that the amount of time and effort put into the strip was not worth what they were getting out of it. The strip ended after only 3 years, on April 15, 1956.

After this, their newspaper career was over, and they would never syndicate a comic strip again. They immediately went back to working at Collier's, though that magazine also ceased publication at the end of 1956. Afterwards, they created a recurring magazine feature "It's All In The Family," which first ran in McCall's and later Good Housekeeping, until it ended in 1988. The first Berenstain Bears book was published in 1962, and would of course spawn the series of books that eclipsed all of their previous cartooning work. Sister wasn't the last time they would attempt a syndicated newspaper comic, however. According to a listing from Editor & Publisher magazine in 1982, a comic strip based on the Berenstain Bears was at one point under development and set to be syndicated by King Features, but never came about.

For more information:

Child's Play: The Berenstain Baby Boom, by Mike Berenstain, Stan and Jan's son

Sister at Stripper's Guide

The Berenstains at The Daily Cartoonist

Team Berenstain part 1, part 2, part 3, and part 4 at the Berenstain Bears Blog

Berenstain cartoon books, early magazine cartoons, and Sister from Collier's Magazine at Mike Lynch's blog

More on the Berenstain cartoon books at Berenstain Bears Collectors