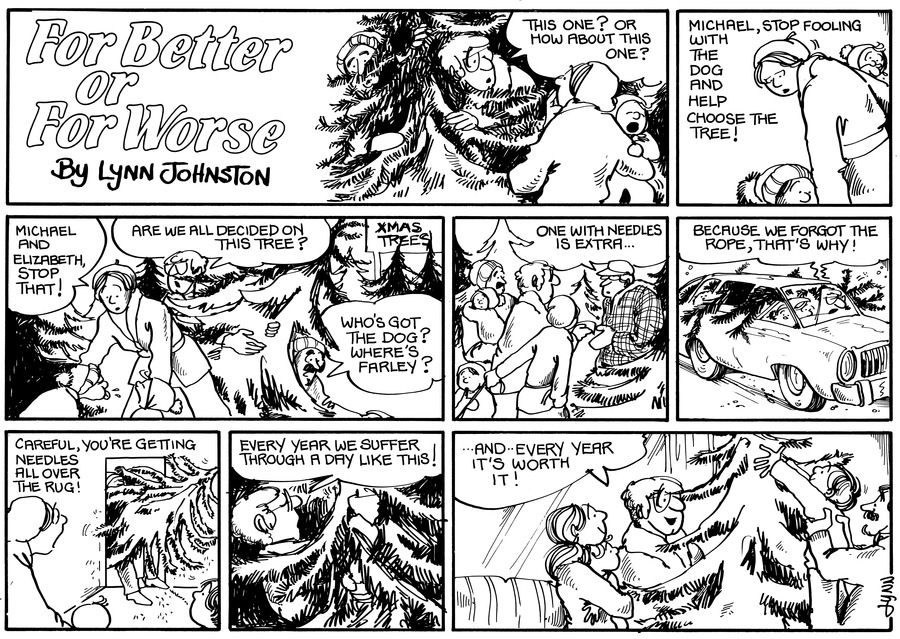

Click the image for a larger version.

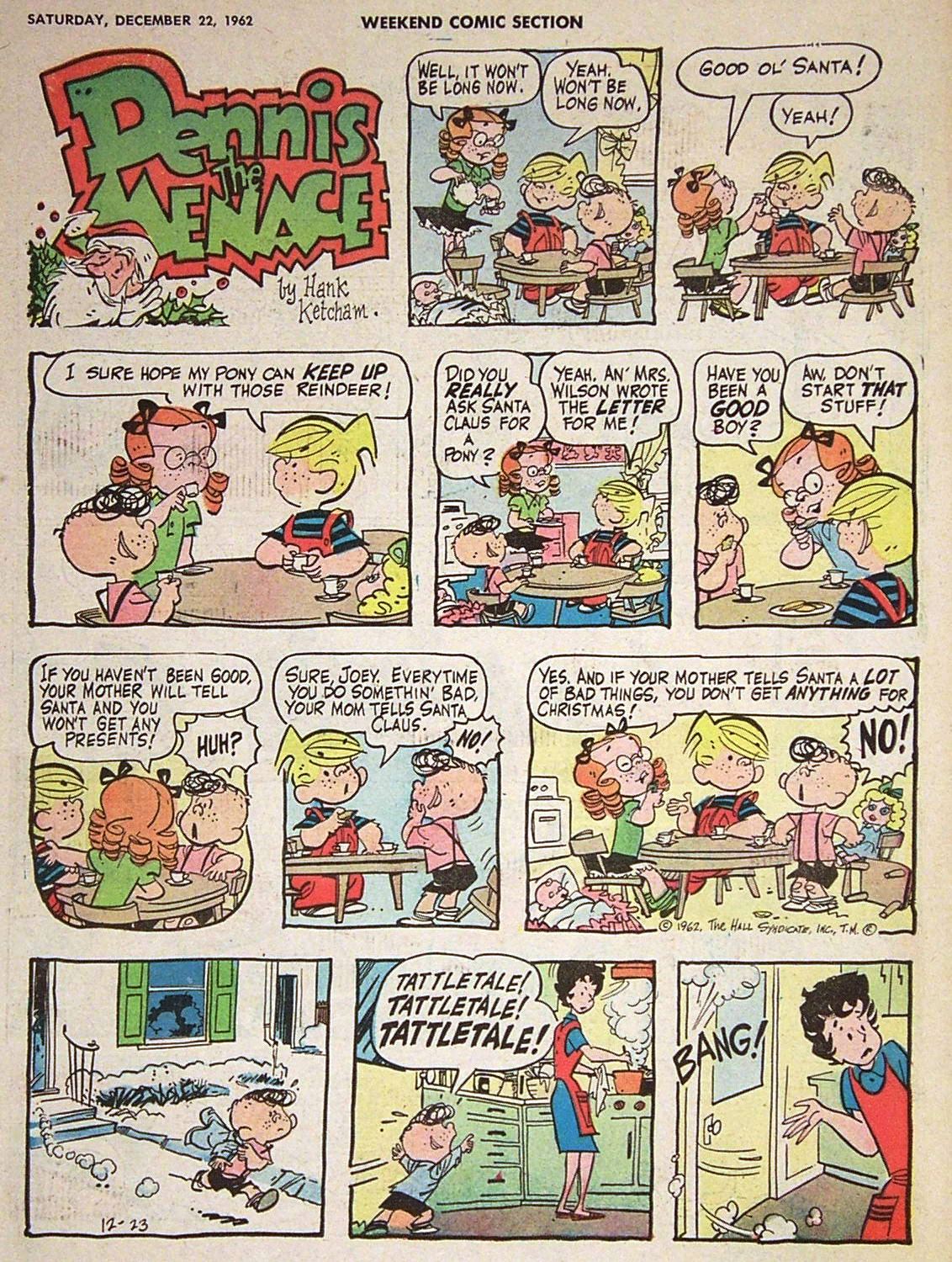

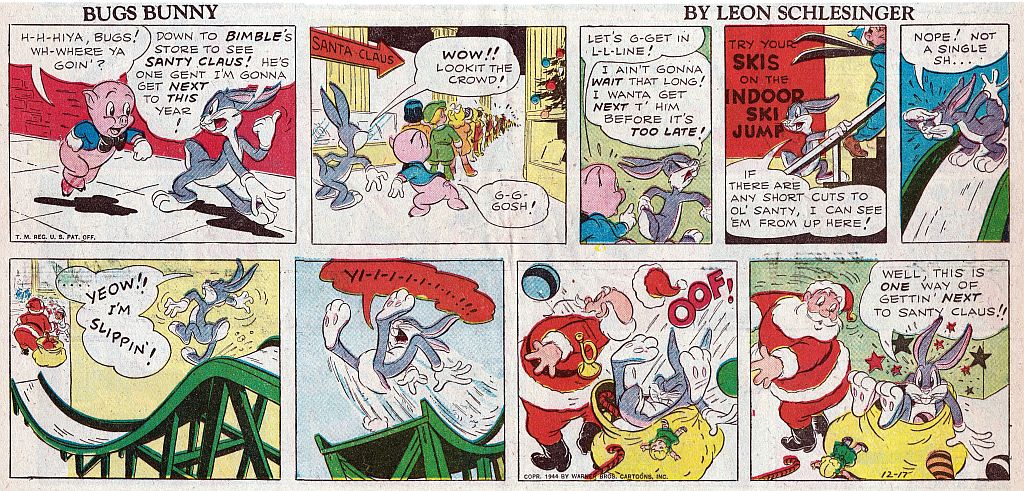

I wonder about Michael's question in the first panel. Does he think that his grandpa is so old that he's actually older than Santa? How old does he think Santa is? Does he suspect that his grandpa might be Santa? Has he already figured out that Santa is a myth, and is trying to find out about its origins?

Or has he just not thought about it at all (which is far more likely)?