As a kid, I was a big fan of the Garfield comic strip. As I've gotten older, read more Garfield, and learned more about the creator of Garfield, Jim Davis, I became less and less enamored with the strip and now see it as generally very boring and repetitive. One of the recurring jokes in Garfield, and the one that recurs the most often, has to do with the fact that Garfield hates Mondays. This is an absurd idea because, as a cat, Garfield doesn't really have any concept of a weekend, or a work week, or any of that, so there's no reason for him to be so hateful of Mondays in particular. That's what makes it funny, I guess. Jim Davis took it a step further, however, and gave Garfield a reason to hate Mondays, as bad things continued to happen to him on that day and that day only. The worst day of all was, of course, Monday the 13th, it being inherently unlucky due to being a Monday, as well as having an unlucky number as the date. As a kid who grew up in the 90s, I figured this was a thing that Jim Davis came up with, and it was unique to Garfield.

This was untrue.

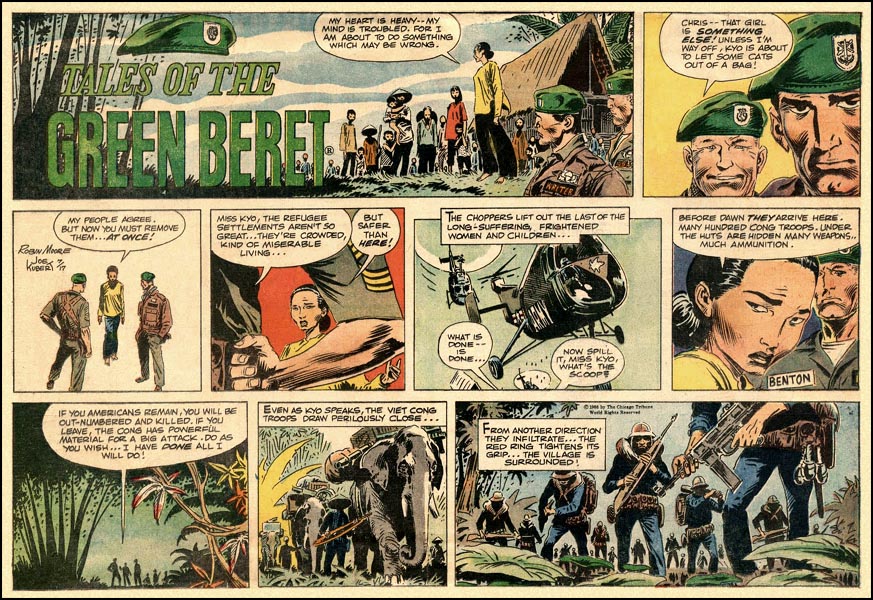

Big George, by Virgil Partch, which I've covered briefly before, was a single panel comic strip that began in 1960. The titular George was a family man who worked at a 9-5 office job, giving him ample reason to hate Mondays. For the first few years of the strip, Mondays never really came up, and most of the humor dealt with George and his family, or his neighbors, or his hobbies. In 1966 and 1967, however, Partch decided to try some new things with the strip. Some new characters were introduced, such as a hippy with long hair that covered most of his body, the family dog and family cat began to talk to each other and other animals though they had previously been mute, and Partch briefly experimented with breaking up the single panel dailies into a four panel format. None of these things really lasted that long, but one thing that did stick was George's newfound hatred of Mondays.

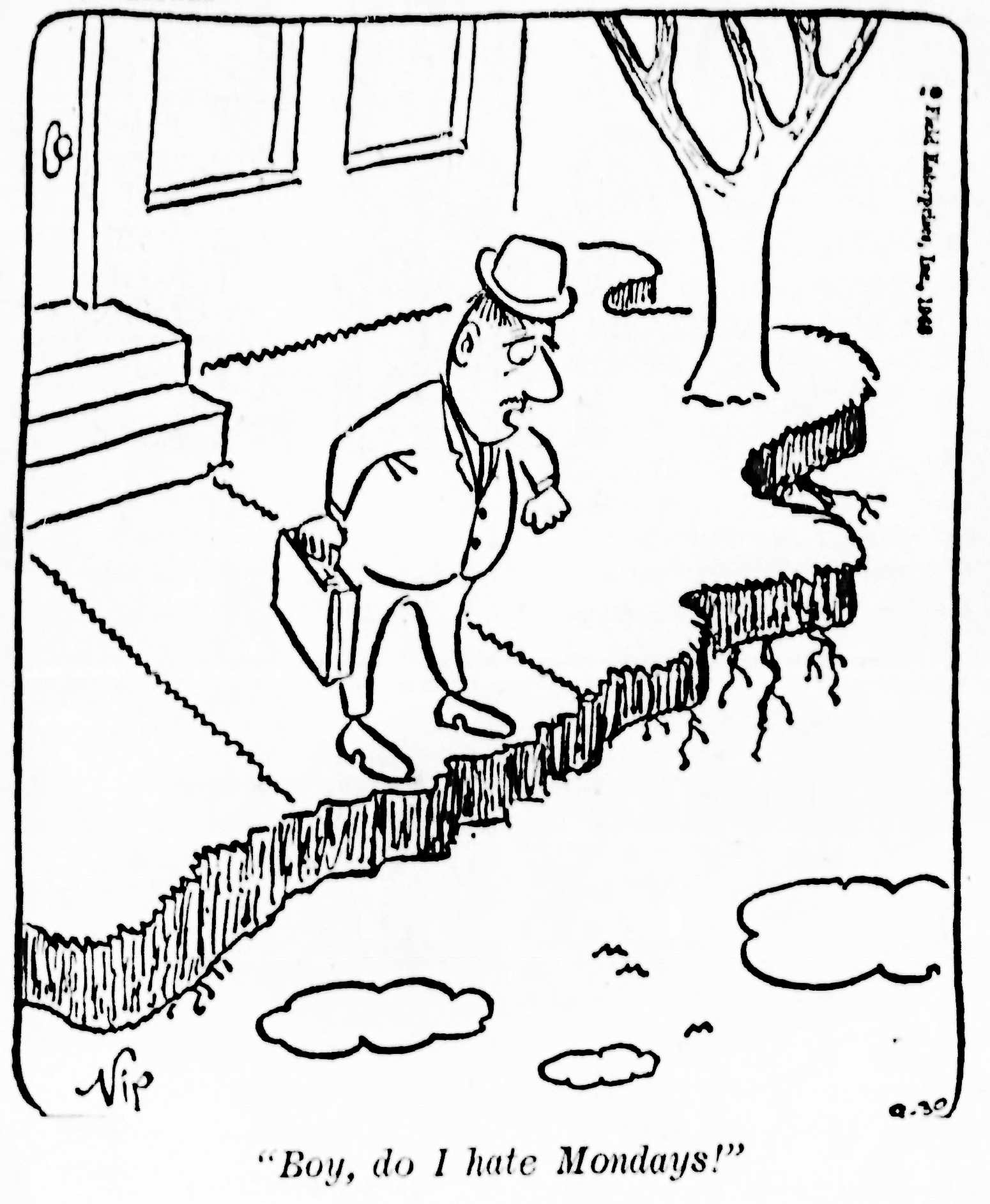

While some sources will tell you that Partch, during this and later periods, had George expressing his distaste for Mondays every week, that isn't necessarily true. The Monday gags were sprinkled throughout the various months, and there are long periods where the day of the week isn't mentioned at all. However, much like what Jim Davis would do with Garfield over a decade later, it wasn't just that George hated going into the office on Monday after the weekend. Horrible, unexpected things would happen to him on that day, such as someone driving their car into his house, or his roof leaking, or a sign falling on him, or a raincloud raining only on him, or a tree that he's trying to cut down not falling over even after it's fully detached from the stump, or getting shipwrecked on a desert island, or even an actual dragon appearing at his doorstep. While the captions would often mention what's going on as well as the fact that it's Monday, on multiple occasions the caption simply read "I hate Mondays!"

It's unfortunate that, while Garfield became famous for being anti-Monday, George had been hating Mondays for at least a decade prior to Garfield's first appearance. Garfield debuted in 1979, and George first stated that he detested Mondays as early as 1966. Big George is also a much funnier strip than Garfield (though that's all a matter of taste, I guess).

For more information:

Big George at Don Markstein's Toonopedia

Virgil Partch at Lambiek Comiclopedia